I don’t know if it’s your cup of tea, but Neovide provides smooth scrolling at arbitrary refresh rates. (It’s a graphical frontend for Neovim, my IDE of choice.)

Programmer in NYC

I don’t know if it’s your cup of tea, but Neovide provides smooth scrolling at arbitrary refresh rates. (It’s a graphical frontend for Neovim, my IDE of choice.)

For some more detail see https://dev.to/martiliones/how-i-got-linus-torvalds-in-my-contributors-on-github-3k4g

It looks like there is at least one work-in-pprogress implementation. I found a Hacker News comment that points to github.com/n0-computer/iroh

Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. If the thinking is that AI learning from others’ works is analogous to humans learning from others’ works then the logical conclusion is that AI is an independent creative, non-human entity. And there is precedent that works created by non-humans cannot be copyrighted. (I’m guessing this is what you are thinking, I just wanted to think it out for myself.)

I’ve been thinking about this issue as two opposing viewpoints:

The logic-in-a-vacuum viewpoint says that AI learning from others’ works is analogous to humans learning from others works. If one is not restricted by copyright, neither should the other be.

The pragmatic viewpoint says that AI imperils human creators, and it’s beneficial to society to put restrictions on its use.

I think historically that kind of pragmatic viewpoint has been steamrolled by the utility of a new technology. But maybe if AI work is not copyrightable that could help somewhat to mitigate screwing people over.

That sounds like a good learning project to me. I think there are two approaches you might take: web scraping, or an API client.

My guess is that web scraping might be easier for getting started because scrapers are easy to set up, and you can find very good documentation. In that case I think Perl is a reasonable choice of language since you’re familiar with it, and I believe it has good scraping libraries. Personally I would go with Typescript since I’m familiar with it, it’s not hard (relatively speaking) to get started with, and I find static type checking helpful for guiding one to a correctly working program.

OTOH if you opt to make a Lemmy API client I think the best language choices are Typescript or Rust because that’s what Lemmy is written in. So you can import the existing API client code. Much as I love Rust, it has a steeper learning curve so I would suggest going with Typescript. The main difficulty with this option is that you might not find much documentation on how to write a custom Lemmy client.

Whatever you choose I find it very helpful to set up LSP integration in vim for whatever language you use, especially if you’re using a statically type-checked language. I’ll be a snob for just a second and say that now that programming support has generally moved to the portable LSP model the difference between vim+LSP and an IDE is that the IDE has a worse editor and a worse integrated terminal.

I pretty much always use list/iterator combinators (map, filter, flat_map, reduce), or recursion. I guess the choice is whether it is convenient to model the problem as an iterator. I think both options are safer than for loops because you avoid mutable variables.

In nearly every case the performance difference between the strategies doesn’t matter. If it does matter you can always change it once you’ve identified your bottlenecks through profiling. But if your language implements optimizations like tail call elimination to avoid stack build-up, or stream fusion / lazy iterators then you might not see performance benefits from a for loop anyway.

I think Picard was willing to sacrifice himself to save the kids. He’s an officer who signed up for a risky job - they are not, and also they’re kids. I think he thought that going with them would slow things down enough to add unacceptable risk for the kids. And they did end up spending a bunch of time cobbling together an apparatus to move Picard during which the lift could have fallen.

When the kids refused to go maybe that changed Picard’s calculation: the advantage of going without him diminishes if they use up time arguing. Or maybe it’s TV writing.

But maybe Picard wasn’t certain that the lift would fall. Or maybe if he’d stayed he would have managed to pull out a Picard move to save himself at the last second - you know, the kind that’s easier to do when there aren’t kids watching. Or maybe, as far as he knew someone might rescue him in time. But yeah, he probably would have died, and the kids’ mutiny was the only out that let him save himself while also trying to be noble.

when relays are blown

when power reserves fail

when life support is gone

gravity plating’s pull is relentless

it will carry on

I also have mixed feelings about Discovery, but for different reasons. I love the characters and character writing. I disagree that the rest of the crew doesn’t get any development - but a lot of that does come in later seasons. My complaints are about the plots. I think season 1 was the most problematic in that respect with progressive improvements over the next two seasons. (I haven’t seen season 4 yet.)

It wasn’t enough to try to take on the entire Klingon war at the same time as introducing a whole new cast. They also had to add an entirely separate, even more threatening crisis?

Making Michael responsible for both starting and ending the war makes you feel like the universe begins and ends on one ship.

We don’t need constant threats of annihilation in the story to be engaged! The most compelling Trek writing has had much lower stakes. When we have had high stakes, like in The Best of Both Worlds and The Dominion War, the writers managed to make us feel like we were seeing a pivotal part of a much larger conflict. They took the time to build up to the big tension, and took the time to play out satisfying resolutions. And they didn’t make it the entire show.

But things got gradually better,

In season 2 they managed to limit themselves to a single major crisis. And they stepped it down from end-of-every-universe to end-of-all-life-in-one-galaxy. But still unbelievably over-the-top. Still too much artificial tension. Still too Discovery- & Michael-centric.

I love Michael, and I enjoy watching her be great at everything. But she can be part of a larger society of amazing people, and still be amazing herself.

And then they stepped it down again to maybe-end-of-what’s-left-of-the-Federation.

In season 3 things slowed down enough, and they spent enough time letting more of the cast develop and drive the story that I felt like I could enjoy the story without gritting my teeth.

But I do have similar feelings: the world-building of what is essentially a whole new galaxy in season 3 feels underdeveloped. I was initially frustrated by what felt like an attempt to distance Discover from Star Trek. Trek is supposed to be about a future utopia - we have enough other works that wallow in dystopia. But it seems like maybe it’s only supposed to be dystopian for one season? The ambitious writing is certainly still there.

I don’t disagree with you about mirror-Georgiou’s participation being unbelievable. The thing where everybody loves Michael to the degree where it becomes their primary motivation is too Mary Sue-like. Again I think that’s at its worst in season 1. OTOH having Michelle Yeoh on the show is a lot of fun so I’m inclined to forgive the stretch in that character arc.

And there is also Nushell and similar projects. Nushell has a concept with the same purpose as jc where you can install Nushell frontend functions for familiar commands such that the frontends parse output into a structured format, and you also get Nushell auto-completions as part of the package. Some of those frontends are included by default.

As an example if you run ps you get output as a Nushell table where you can select columns, filter rows, etc. Or you can run ^ps to bypass the Nushell frontend and get the old output format.

Of course the trade-off is that Nushell wants to be your whole shell while jc drops into an existing shell.

I’m a fan! I don’t necessarily learn more than I would watching and reading at home. The main value for me is socializing and networking. Also I usually learn about some things I wouldn’t have sought out myself, but which are often interesting.

This is what I use. Or if you don’t need image/PDF embedding or mobile support then VimWiki is a similar solution that is FOSS.

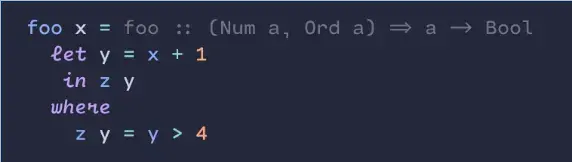

That’s a very nice one! I also enjoy programming ligatures.

I use Cartograph CF. I like to use the handwriting style for built-in keywords. Those are common enough that I identify them by shape. The loopy handwriting helps me to skim over the keywords to focus on the words that are specific to each piece of code.

I wish more monospace fonts would use the “m” style from Ubuntu Mono. The middle leg is shortened which makes the glyph look less crowded.

One of my favorites is from Sisko, but I guess this one is more of a soliloquy than a dialogue,

The trouble is Earth! On Earth, there is no poverty, no crime, no war. You look out the window of Starfleet Headquarters and you see paradise. Well it’s easy to be a saint in paradise, but the Maquis do not live in paradise! Out there, in the Demilitarized Zone, all the problems haven’t been solved yet! Out there, there are no saints! Just people! Angry, scared, determined people, who are going to do whatever it takes to survive, whether it meets with Federation approval or not!

git rebase --onto is great for stacked branches when you are merging each branch using squash & merge or rebase & merge.

By “stacked branches” I mean creating a branch off of another branch, as opposed to starting all branches from main.

For example imagine you create branch A with multiple commits, and submit a pull request for it. While you are waiting for reviews and CI checks you get onto the next piece of work - but the next task builds on changes from branch A so you create branch B off of A. Eventually branch A is merged to main via squash and merge. Now main has the changes from A, but from git’s perspective main has diverged from B. The squash & merge created a new commit so git doesn’t see it as the same history as the original commits from A that you still have in B’s branch history. You want to bring B up to date with main so you can open a PR for B.

The simplest option is to git merge main into B. But you might end up resolving merge conflicts that you don’t have to. (Edit: This happens if B changes some of the same lines that were previously changed in A.)

Since the files in main are now in the same as state as they were at the start of B’s history you can replay only the commits from B onto main, and get a conflict-free rebase (assuming there are no conflicting changes in main from some other merge). Like this:

$ git rebase --onto main A B

The range A B specifies which commits to replay: not everything after the common ancestor between B and main, only the commits in B that come after A.

Just a guess: I think Inform fits your description

Deep Space 9 is a different animal. It's fantastic if you like a political drama. There is less space adventure than the other series.

It looks like it's made by the same team that made Journey

It scrolls smoothly, it doesn’t snap line by line. Although once the scroll animation is complete the final positions of lines and columns do end up aligned to a grid.

Neovim (as opposed to Vim) is not limited to terminal rendering. It’s designed to be a UI-agnostic backend. It happens that the default frontend runs in a terminal.